Are projects the only reasonable way to develop products? Do you, as a portfolio manager, use projects as your only means to add value?

Projects “Cargo Cult”

According to the PwC global project management report, 97% of organizations believe that project management is critical to business performance and organizational success. However, the trust that organizations place in such projects backfires when managers, because projects worked for them in the past, start to automatically create projects for every possible change.

For example, an organization decides to create a commercial software product that would automate creation of expense notes for traveling employees:

The product manager (PdM): “I would like to create a project to deliver the first version of my product. The business case for my product has been approved by senior management.”

PMO: “We will appoint a project manager and start a project.”

The new project manager (PjM): “I am desperately trying to figure out the scope and constraints of this project, but there is just not enough data.”

The product manager (PdM): “Here are some features we would really like to have in the first version. We could have a feature to scan paper bills, optical text recognition to convert them into text, and perhaps an integration with some ERP plus a bunch of small features. Here’s the full list.”

The new project manager (PjM): “I will put these features in the scope statement. As we do not have any timeline, I will set an artificial deadline to keep the team “motivated” to deliver. Now, let’s kick off!”

Needless to say, this project will not deliver best value to the customers and, as a result, to the performing organization. In addition to poor business results, the teams will likely be demotivated, and the future of the product will not be the best. (Hint: Never do such projects in real life!)

Instead of being a useful means to deliver value, such project management practices become a ‘cargo cult.’ Because projects are supposed to have a scope statement, budgets, and timelines, managers would start enthusiastically defining them – and, in case of absence of the real data about project scope and constraints, they would provide artificial or unverified data just to keep the projects ‘SMART.’ In reality, these projects are very far from being smart.

Alternatives for ‘Bad Projects’

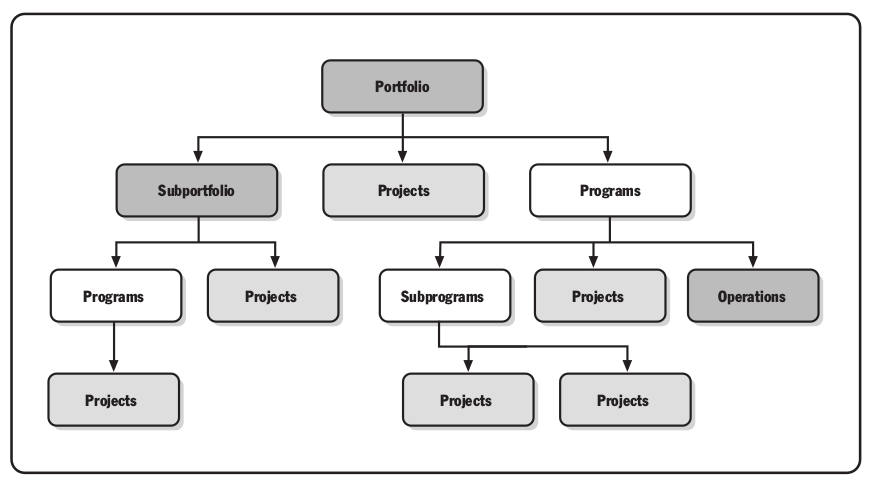

Back to portfolio management. Contrary to popular belief, portfolios do not consist solely of projects. Project portfolio management defines a portfolio as a collection of projects, programs and operations, managed as a group to achieve strategic objectives.

It is up to you, as a portfolio manager, to decide what would be the best means to achieve the goals of your organization.

For example, in the situation above, you could start a team to work in a continuous delivery mode as software development operations. The team would deliver small increments, and continuously adjust the course based on user feedback.

(source: PMI standard for Portfolio management, 3rd edition)

Instead of a ‘bad’ software or IT project, you could choose DevOps to deliver value to your portfolio. In other cases, instead of running a large ‘bad’ project with a lot of interdependencies, consider starting a program to coordinate several individual smaller projects.

Not All Projects Are ‘Bad’

There are a lot of alarming statistics on the Internet about the failure rates of projects. Question: Does this mean that projects are to be avoided in your portfolio?

Further analysis of the statistics suggest that it does not. In high-performing organizations, a reassuring 89% of projects meet their objectives in contrast to low-performers, where only 36% of projects succeed. There is nothing ‘flawed’ in the concept of the projects, but you have to have the quality of the high-performers to successfully run projects.

In a high-performing portfolio, not only the projects are managed correctly, but also – and in my opinion more importantly – the right projects are managed. ‘Good’ projects have clear, SMART goals, reasonable constraints, adequate resources, and are aligned with the strategy of your organization.

One of the critical factors is the project size. Statistics suggest that small projects are eight times more successful than large projects!

For example, to make sure your EU customer data is properly protected, you would like your IT systems and business processes to comply with GDPR by 25th of May 2018.

You perform an audit of your systems and identify all the potential gaps you need to address. You make sure that legal, security, IT, software, and quality control teams, understand the challenge and have sufficient resources to move forward. You also have the full support of executive management. Your preliminary estimation shows that the total cost would be about 150-300kEUR.

In this case, starting a project could be the right choice to achieve compliance on time.

Conclusion, or When and When Not to Start a Project

Having ‘bad’ projects in your portfolio can lead to poor business results, low team morale, and sub-optimal product decisions.

Do not include such projects in your portfolio. Instead, consider other possibilities, such as creating a program and breaking the big project down into smaller projects. Sometimes, you will want to start operations to achieve the business objective instead of having a project or a sequence of projects.

Start a project when:

- There is a clear mid or long-term goal to achieve

- There are constraints to be met

- Coordinated work of a (cross-functional) team is required

- The size is reasonable to manage as one project

Do not start a project when:

- The goal is not clear or a lot of change is expected. Consider an investigation project first, or continuous elaboration and delivery operations

- There are no known time/cost constraints. Consider operations;

- The effort is too large. Consider starting a program.

Title photo by JOSHUA COLEMAN on Unsplash